Treedown: A Simple Notation for Syntax

12 May 2017

This is the first of a series on the Lowfat Treebanks (Nestle1904, SBLGNT), which were designed to make it easier to visualize and query Greek sentences.

This post focuses on visualization. The Lowfat treebanks have three stylesheets that provide three different ways to visualize a treebank, but this post will focus on Treedown, a visualization that can also be used as a text-based notation. It will also mention Boxwood and Brackets, two other stylesheets related to Treedown.

What is Treedown?

The right notation makes it easier to think clearly.

One of the reasons commentaries are hard to read is that they attempt to describe the syntax of Greek sentences using natural language, which is not always the best way to describe abstractions. It would be much harder to think clearly about math without mathematical notation and much harder to think clearly about a sonata without musical notation. Treedown is designed to make it easier to think clearly about the syntax of sentences using a notation that is precise, concise, and easy to read and write. Treedown does not try to be the ultimate linguistic representation for all purposes, it simply tries to describe the basic structure of a sentence without getting in the way of the text.

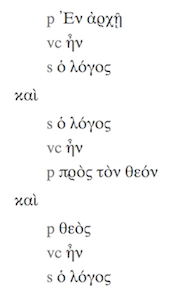

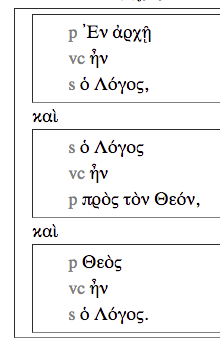

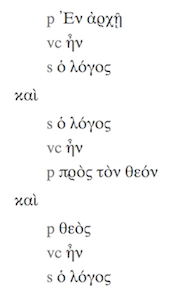

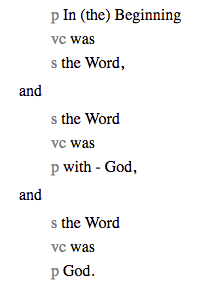

Here is an example of Treedown, showing John 1:1 in Greek and in English.

|

|

The labels used in the above diagram are:

- ’s’ = subject

- ‘vc’ = copulative verb (a verb like ‘is’ that binds subject to predicate)

- ‘p’ = predicate

Here are some advantages of Treedown over some other approaches to visualization:

- Treedown is minimal - the text is prominent because syntax annotation does not overwhelm the text. The text is easier to read as text, and patterns in grammatical structure are easier to see.

- In Treedown, it is easy to represent large sentences. It also scales sentence complexity, representing both simple sentences and complex sentences well.

- Treedown can be written with any text processor, and does not require any particular software. This makes it much easier to discuss various understandings of a text in email or on forums, or to log issues against a treebank suggesting an additional interpretation or correcting an existing interpretation.

Treedown does not prescribe a particular set of labels. My posts will usually use the role attributes we use in the Lowfat Trees:

| Label | Part of Speech |

|---|---|

| S | Subject |

| V | Verb |

| IO | Indirect Object |

| O | Object |

| O2 | Second Object |

| VC | Verbal Copula |

| P | Predicate |

| ADV | Adverbial |

We are in the process of adding additional labels to better account for adjuncts, interjections, vocatives, etc. Another project could choose a different set of labels.

Treedown and Bracket Notation

Treedown can be seen as an alternate form of a bracketed notation familiar to many linguists. Consider this representation of the same verse:

[[[p In (the) Beginning][vc was][s the Word]]

[cj and][[s the Word][vc was][p with - God]]

[cj and][[s the Word][vc was][p God]]]

In this example, a bracket without a label is equivalent to a clause, and a bracket with a label is a constituent with a defined role in a clause. In Treedown, an indentation level is equivalent to a bracket and the outer bracket that defines the sentence as a whole is omitted. At any indentation level, the constituents can be shown vertically instead of horizontally. Let’s convert this to Treedown. First, let’s remove the outer brackets and put each bracketed region on one line:

[[p In (the) Beginning][vc was][s the Word]]

[cj and]

[[s the Word][vc was][p with - God]]

[cj and]

[[s the Word][vc was][p God]]

Now let’s replace the outer brackets for each clause with an indentation level and line up the constituents in each clause vertically:

p In (the) Beginning

vc was

s the Word

cj and

s the Word

vc was

p with - God

cj and

s the Word

vc was

p God

In the Lowfat Trees, our Treedown does not currently display labels for conjunctions (this is a matter of some debate, a tradeoff between explicitness and figure/ground issues when reading a text).

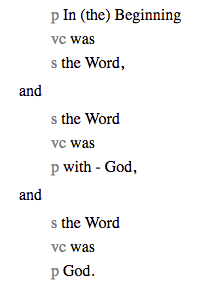

The equivalence of Treedown and bracket notation has some practical ramifications. Not only does it guarantee that Treedown is well defined, it means that we can convert our notation to bracket notion in order to use a variety of existing tools. For instance, here is that same sentence as displayed using this Syntax Tree Generator, taking the bracket notation as input:

Note how similar the structure of this diagram is to the structure of the corresponding Treedown.

Wait! What are we trying to represent?

The idea for Treedown came from a series of experiments writing stylesheets for the Lowfat Treebanks. Since we have syntax trees for the entire Greek New Testament represented in XML, I developed a variety of CSS stylesheets, looking at simple and challenging sentences in John 1, Luke 1, and Ephesians 1. Some formats made it hard to show the structure of a long and complex sentences at all. Some did a good job of grouping related words, others did not. Some were much easier to read than others. Some could be written easily with a word processor, others relied on graphics that made this impossible.

Here are some insights that came from that experiment:

- Whitespace can be used as the primary mechanism for modeling hierarchical structure.

- Most sentences can be made much clearer by aligning conjunctions and representing the role of each constituent in a clause.

- The current modeling of adjuncts in the Lowfat treebanks is not adequate - see this issue and the following discussion.

- Negation, vocatives, interjection, ellipsis, and coordination also need better representations. This will be discussed in future posts.

- Word order issues are important to consider. This issue will be discussed in future posts.

- Where explicit relationships are not stated for adjuncts and other constructions, the structure can still be shown in a useful way using Boxwood, a variation on Treedown that marks clause boundaries with borders. This is discussed in a following section.

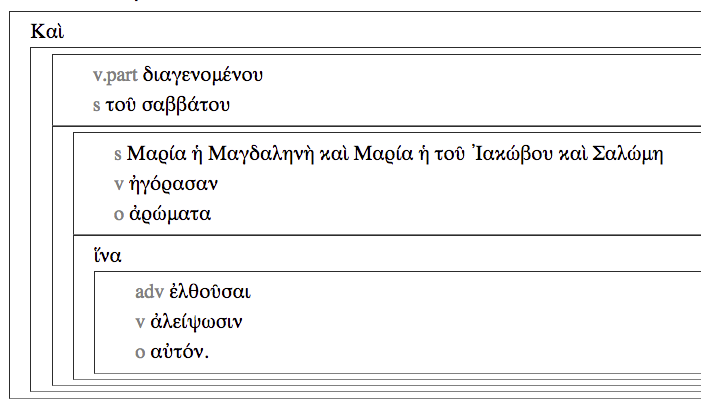

The following sentence from Mark 16 illustrates some of these issues. Here it is in English and Greek:

+ s The Sabbath

v.part having passed,

s Mary Magdelene and Mary the mother of James and Salome

v bought

o spices

+ in order to

+ v.part go and

v anoint

o him

+ v.part διαγενομένου

s τοῦ σαββάτου

s Μαρία ἡ Μαγδαληνὴ καὶ Μαρία ἡ τοῦ Ἰακώβου καὶ Σαλώμη

v ἠγόρασαν

o ἀρώματα

+ ἵνα

+ v.part ἐλθοῦσαι

v ἀλείψωσιν

o αὐτόν.

In this notation, the letters label the verb and its arguments - subject and object, in this case. The + label is used for adjuncts:

an adjunct is an optional, or structurally dispensable, part of a sentence, clause, or phrase that, if removed or discarded, will not otherwise affect the remainder of the sentence.

These clauses are optional in precisely this sense: we can simplify this sentence by removing the adjuncts without changing the basic meaning of the main clause, producing this simpler sentence: “Mary Magdelene and Mary the mother of James and Salome bought spices”. The clause starts with a temporal adjunct identifying the time that they bought spices (“the Sabbath having passed”). It ends with a causal adjunct establishing the reason that they bought spices (“in order to go and anoint him”). Modeling these as adjuncts simplifies the notation and makes relationships more explicit.

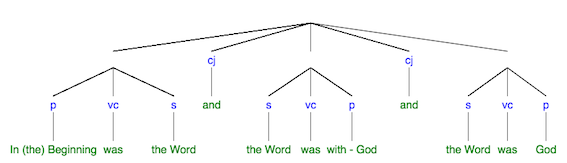

Boxwood

Currently, many relationships in the Lowfat trees are represented strucurally via nested clause structures, not via roles. That means that the structure of many sentences is not clear without showing the clause boundaries more explicitly. Boxwood is a stylesheet that represents Lowfat trees using Treedown conventions, but adding these clause boundaries. Here is the current representation of Mark 16:1 in Boxwood:

Although the adjuncts are not explicitly labeled, the structure is nevertheless clear. Boxwood is not as useful for sentences like John 1:1, where Treedown is already quite clear for the Lowfat trees:

Over time, we hope to make all relationships more explicit, which may well make Boxwood less useful. In the meantime, Boxwood is also helpful as we consider how to simplify the current representation.

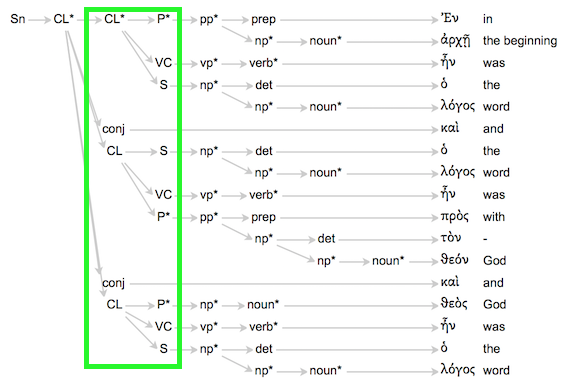

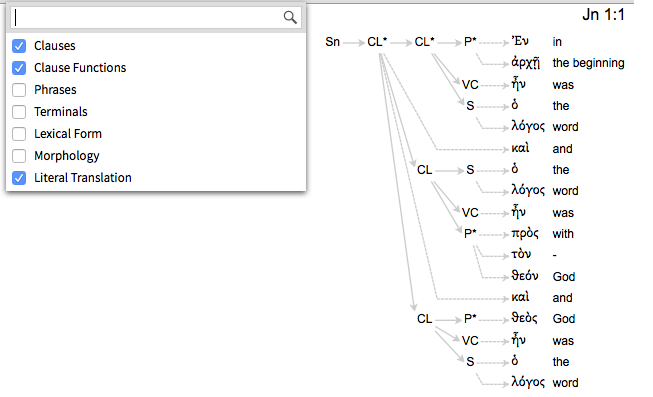

Comparison to Cascadia Syntax Trees

The Treedown representation shows much less detail than the Cascadia Syntax Trees used in in Logos 7. In the following Cascadia display, the green box indicates the portions of the structure that are represented in Treedown:

We can use the configuration dialog to trim that down to just clauses and clause functions, which gives us a representation closer to the granularity of the Treedown representation we have been working with:

Compare that to the representation of the same sentence we saw at the beginning of this post:

|

|

To see the relationship betweeen these two representations, look at the labels for each line in the Treedown, from top to bottom, and look for the corresponding node in the Cascadia representation.

Internally, Lowfat trees have a representation for most of the nodes in the Cascadia graph, and they are available for queries, but Treedown does not display them all. The nodes on the left-hand side of the green box are present in every syntax tree, so they are redundant. The syntax of noun phrases and prepositional phrases is not difficult for most human beings, so Treedown simplifies the display by not showing those nodes. As a result, the natural grouping of words is easier to see in Treedown.

The syntax of noun phrases and prepositional phrases is also relatively simple for computers. At some point, we hope to explore combining Treedown with a simple phrase parser to produce new treebanks that contain phrase structure and morphology.

Implementation: XML and CSS

This section can be safely skipped by anyone who doesn’t need to know how to write and use stylesheets with XML. But it might help explain why XML makes it easier to visualize treebanks in various formats.

Earlier, I mentioned that the Lowfat Trees contain much more detail than Treedown displays. The Lowfat Trees are implemented as XML files. For instance, here is the Lowfat representation of John.

CSS (Cascading Stylesheets) is a stylesheet language for XML and HTML. The views discussed in this post are implemented using CSS. If you are not familiar with CSS stylesheets, you may be surprised how simple it is to use this approach. For instance, the Treedown stylesheet adds spacing for a wg element, which represents a word group, if its class attribute is ‘cl’, which indicates a clause. It also ensures that each clause occurs as a block:

wg[class=cl] {

padding-top: 0.25em;

padding-bottom: 0.25em;

padding-left: 1em;

display: block;

}

If a word group has a role attribute, the role is displayed in small grey letters before the word group itself:

wg[role]::before {

color: grey;

content: attr(role);

size: small;

}

Similar simple rules are used to define each aspect of the Treedown format.

The Boxwood stylesheet draws borders around the left, top, and bottom of each clause:

wg[class=cl] {

padding-top: 0.25em;

padding-bottom: 0.25em;

padding-left: 1em;

display: block;

border-left: 1px inset grey;

border-top: 1px inset grey;

border-bottom: 1px inset grey;

}

The Boxwood stylesheet is used together with the Treedown stylesheet.

The Brackets stylesheet uses ‘[’ and ‘]’ characters to mark the beginning and end of a clause instead of using borders.

wg[class=cl]::before {

content: "[";

color: cadetblue;

size: small;

}

wg[class=cl]::after {

content: "]";

color: cadetblue;

size: small;

}

This is just a teaser, not a tutorial on CSS, but it gives a flavor for the way CSS works with data stored as XML.

Summing up

Treedown is a notation that makes it easier to think clearly about the structure of sentences. It uses hierarchy and word groups to show this structure while still allowing the text to be prominent, and is easy to read and write. It can be produced from a much more detailed XML structure using a CSS stylesheet. Treedown is designed to be easy to learn and easy to read, without getting in the way of the text. It focuses on the structure of a sentence, providing just enough structure to guide the reader and not get in the way of the text - and I suspect this is just enough structure to guide software in constructing treebanks similar to the Lowfat Treebanks.

Treedown is new, and it is prompting us to consider ways to restructure our Lowfat trees, a process that will probably require significant time. I have mentioned many issues - including word order, coordination, ellipsis, negation, interjections, and vocatives - without addressing them. I have solutions to some of these, but not all, and am actively playing with ways to use Treedown to take these issues into account. These issues will be discussed in future posts.